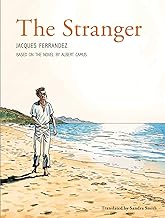

Albert Camus' The Stranger has long stood as a pillar of existentialist and absurdist literature, challenging readers with its stark portrayal of a man detached from societal norms. For decades, its philosophical depth was confined to the printed word. Now, a new medium has emerged to reinterpret this classic: the graphic novel. The adaptation titled The Stranger: The Graphic Novel offers a unique visual gateway into Camus' world, making the complex themes of absurdism and alienation more accessible than ever before. This visual retelling is not merely an illustrated book; it is a profound re-examination of Meursault's journey through the lens of sequential art.

The decision to adapt such a seminal work into a graphic novel adaptation is a bold one. It speaks to the evolving nature of how we consume and interpret classic narratives. Where the original text relies on Camus' sparse, detached prose to convey Meursault's emotional numbness, the graphic novel uses visual cues—the starkness of the Algerian sun, the emptiness in a character's eyes, the oppressive silence between panels—to evoke the same sense of existential dread. This format invites both longtime admirers of Camus and new readers to engage with the story on a different, often more immediate, sensory level.

Why Adapt The Stranger into a Graphic Novel?

The core philosophy of Camus' absurdism centers on the conflict between the human desire for meaning and the universe's silent indifference. Translating this abstract conflict into images requires a deft hand. A successful graphic novel adaptation must do more than depict events; it must visualize the *feeling* of absurdity. The artist's choices in style, color palette, and composition become critical tools for expressing what Camus articulated in prose. For instance, the relentless, bleaching sun of Algiers, a key motif in the novel, can be rendered as a tangible, oppressive force on the page, visually communicating the external world's assault on Meursault's consciousness.

This adaptation also serves as a bridge. For readers who may find dense philosophical texts daunting, the graphic novel format provides a more approachable entry point. The visual narrative guides them through the plot and emotional landscape, priming them to grasp the deeper philosophical questions. Conversely, for scholars and fans of the original, the graphic novel offers a fresh perspective, highlighting details and emotional nuances that might have been glossed over in a purely textual reading. It becomes a new text to be analyzed, a dialogue between the original work and its visual interpretation.

Visualizing Meursault's Alienation

Meursault, the protagonist of The Stranger by Albert Camus, is famously inscrutable. His emotional flatness and refusal to conform to societal rituals are the engine of the story. In prose, this is conveyed through his first-person narration. In a graphic novel, the artist faces the challenge of depicting a man who claims to feel very little. This is often achieved through subtlety: a consistent, neutral facial expression; body language that is closed off or detached from others in the panel; and the use of space. By placing Meursault alone in large, empty panels or contrasting his stillness with the animated gestures of those around him, the artist can visually articulate his profound alienation.

The pivotal moments—his mother's funeral, the murder on the beach, the trial—gain a new dimension. The tension of the murder scene, for example, is no longer just described as heat and glare; it is shown. The reader sees the sun's glare as a physical distortion on the page, feels the claustrophobia of the moment through tight panel layouts. This visual immersion can make Meursault's actions and their consequences feel more visceral, forcing the reader to confront the absurdity of the event in a new way.

The Graphic Novel as a Philosophical Medium

Graphic novels and comics have matured into a legitimate medium for exploring complex philosophical ideas. The fusion of text and image allows for a multifaceted exploration of themes like existence, morality, and freedom. In adapting The Stranger, the creators join a tradition of literary graphic novels that treat source material with serious artistic and intellectual respect. The format's inherent ability to show simultaneous events (through split panels) or juxtapose internal thought with external reality (through layered imagery) is perfectly suited to a story about the gap between personal experience and societal judgment.

Furthermore, the reading experience of a graphic novel is inherently different. The pace is controlled not just by words, but by the size and sequence of panels. A reader may linger on a single, powerful image of Meursault in his cell, contemplating the absurdity of his fate, in a way that mimics meditation on a philosophical point. This controlled, visual pacing can deepen the reader's engagement with the story's existential questions.

Who Should Read This Adaptation?

This classic literature comic adaptation is valuable for a wide audience:

- Students and Educators: An excellent companion to the original text, helping to visualize setting, character, and symbolism, making class discussions more dynamic.

- Fans of Graphic Narratives: Readers who appreciate the art of storytelling through sequential art will find a masterfully executed, thought-provoking work.

- New Readers to Camus: Those intrigued by existentialism but hesitant about classic literature will find an accessible and compelling introduction.

- Existing Camus Enthusiasts: A must-have for collectors and scholars, offering a new interpretive lens on a familiar masterpiece.

The graphic novel version of The Stranger does not seek to replace Camus' original work. Instead, it complements and converses with it. It stands as a testament to the enduring power of the story and its ideas, proving that the questions Camus raised about life, meaning, and authenticity are timeless and adaptable to new forms of expression.

Conclusion: A New Way to Experience the Absurd

The release of The Stranger: The Graphic Novel is a significant event in the world of Albert Camus adaptations. It successfully translates the haunting, sun-drenched alienation of the original into a powerful visual language. By doing so, it reaffirms the novel's status as a cornerstone of existential thought while simultaneously pushing the boundaries of how we define literary adaptation. Whether you are revisiting Meursault's story or encountering it for the first time, this graphic novel promises a profound and visually stunning journey into the heart of the absurd. It demonstrates that some stories are so fundamental to our understanding of the human condition that they demand to be retold, reimagined, and seen through new eyes.