Published in 1946, Albert Camus' The Stranger (L'Étranger) stands as a monumental pillar of 20th-century thought. More than just a novel, it is a philosophical treatise disguised as a simple, stark narrative. For many readers, their first encounter with Meursault, the novel's famously detached protagonist, is a disorienting and unforgettable experience. This existentialist fiction challenges our deepest assumptions about meaning, morality, and society's expectations. If you're seeking to understand the core of Camus' philosophy of the absurd, there is no better starting point than this concise, powerful work.

The Historical and Philosophical Bedrock of The Stranger

To fully appreciate The Stranger, one must consider the world from which it emerged. Camus wrote the novel during and in the immediate aftermath of World War II, a period of profound disillusionment and shattered certainties. The old systems of belief—in God, in progress, in a rational universe—had collapsed for many intellectuals. Into this void stepped existentialism and its close cousin, the philosophy of the absurd, which Camus helped define. The novel is not merely a story set in Algeria; it is a direct product of its time, a literary response to a world that had lost its sense.

Camus himself was a key figure in this philosophical movement, though he often resisted the "existentialist" label. His concept of the absurd is central to The Stranger. The absurd, for Camus, is the conflict between the human need for meaning and the universe's silent indifference. Meursault embodies this conflict. His actions, or rather his inactions and his startling honesty, highlight the gap between societal rituals (like mourning a mother) and genuine, felt experience. Reading this absurdist novel today, its themes feel remarkably contemporary, speaking to anyone who has ever questioned the script they are expected to follow.

Deconstructing Meursault: The "Stranger" in Society

The character of Meursault is the engine of the novel's power. He is not a villain, nor is he a hero in any traditional sense. He is an honest man in a world that operates on unspoken rules and performative emotion. His famous opening line—"Mother died today. Or, maybe yesterday; I can't be sure"—immediately establishes his alienation. He does not cry at his mother's funeral, he goes to a comedy film the next day, and he forms a relationship with Marie largely based on physical attraction.

Society judges Meursault not for the murder he commits—which is almost presented as an accident of sun and circumstance—but for his failure to play his part in the social theater. The trial becomes less about the facts of the case and more about his character, his soul. He is condemned for his indifference to his mother, for his atheism, for his refusal to express remorse in the way the court expects. In this way, Camus critiques a society that values conformity over truth, performance over authenticity. Meursault's ultimate awakening to the "gentle indifference of the world" in his prison cell is the climax of his journey toward an authentic, albeit bleak, form of freedom.

Why a Vintage Edition of The Stranger Enhances the Experience

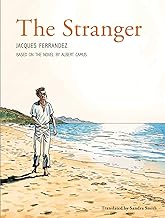

There is a particular charm and authenticity in reading a classic like The Stranger in a period-appropriate format. Seeking out a vintage book or a specific edition, such as the Vintage paperback, connects the reader more directly to the novel's history. Holding a book from the mid-20th century, feeling its paper, and seeing its typography can transport you closer to the moment of its creation and initial reception.

For collectors and serious readers, a vintage edition is more than a reading copy; it's a piece of literary history. It serves as a tangible link to the post-war intellectual climate that shaped Camus and his readers. When you read from a vintage paperback of this 1946 novel, you are engaging with the object as it was first encountered by audiences, adding a layer of context that a modern reprint cannot fully replicate. It reminds us that this was a contemporary, even radical, work in its time.

The Stranger's Enduring Legacy in Modern Culture

The influence of The Stranger Albert Camus extends far beyond the realm of classic literature syllabi. Its DNA can be found in countless films, novels, and philosophical discussions. The archetype of the emotionally detached anti-hero, from Holden Caulfield to characters in modern cinema, owes a debt to Meursault. The novel's central question—how to live an authentic life in a world devoid of inherent meaning—remains one of the defining questions of modern existence.

Camus did not provide easy answers. Instead, The Stranger forces the reader to sit with the discomfort of the absurd. It invites us to question the automatic pilot on which we often live our lives. Why do we do the things we do? Are our emotions always genuine, or are they sometimes performances? In an age of curated social media personas and intense pressure to conform, Meursault's brutal honesty, however unsettling, feels like a radical and necessary counterpoint.

How to Approach Reading The Stranger Today

If you are coming to The Stranger for the first time, or returning to it after many years, here are a few lenses through which to view it:

- As a Philosophical Experiment: Don't just read for plot. Ask yourself: What is Camus trying to demonstrate about human nature and society through Meursault's experiences?

- As a Historical Document: Research the context of French Algeria and post-WWII Europe. Understanding the setting deepens the social critique at play.

- As a Mirror: Which of Meursault's reactions disturb you the most? Your discomfort is likely a clue to your own deeply held, often unexamined, beliefs about how life "should" be lived.

Whether you are a student of philosophy, a lover of powerful prose, or a collector of significant editions, The Stranger demands and deserves engagement. It is a book that does not change, but has a remarkable capacity to change its readers, challenging them to confront the fundamental strangeness of being human.