When readers first encounter The Stranger by Albert Camus, they are often struck by the stark, emotionless narration of its protagonist, Meursault. Published in 1942, this cornerstone of existentialist novel literature is frequently summarized as a tale of absurdism, a man condemned not for murder but for his failure to cry at his mother's funeral. Yet, to confine our understanding to this synopsis is to miss the profound and unsettling questions the novel continues to pose to every generation. This guide aims to move beyond the standard analysis of absurdism, exploring why The Stranger remains a vital, challenging, and deeply relevant text in the 21st century.

Albert Camus, a Nobel laureate often associated with existentialist philosophy (though he preferred the term "absurdist"), crafted in The Stranger a mirror for the modern condition. The novel's power lies not in grand pronouncements but in its chillingly simple prose and the void it exposes within societal rituals. Meursault's crime is one of authenticity in a world demanding performative emotion. As we delve into this modern classic, we will uncover the layers that make it more than just a philosophical fiction assignment, but a personal confrontation with meaning, freedom, and the sun-drenched indifference of the universe.

The Unsettling Heart: Meursault's Authenticity vs. Society's Script

Meursault is literature's most famous "stranger," an outsider not by choice but by ontological design. His famous opening line, "Mother died today. Or, maybe yesterday; I can't be sure," immediately establishes his disconnect from expected emotional responses. Critics and readers often label him as apathetic or amoral. However, a deeper reading suggests Meursault represents a radical form of honesty. He refuses to lie, even to save himself. He won't claim to have felt grief he didn't feel or believe in a God he doesn't perceive.

The trial scene is the brilliant core where Camus dissects society's machinery. The prosecutor successfully argues that Meursault is guilty of a crime against the human heart—his lack of tears at the funeral is presented as evidence of a soul capable of murder. This conflation of private feeling with public morality is the novel's central critique. Society, Camus argues, often condemns the non-conformist more harshly than the actual transgressor. Meursault's ultimate awakening on the eve of his execution—his passionate embrace of the "benign indifference of the universe"—is not a moment of nihilistic despair, but a liberating acceptance of the absurd condition, making him, paradoxically, more alive than the judging crowd. For a comprehensive exploration of this pivotal character and the philosophy he embodies, our analysis The Stranger Albert Camus provides a detailed character study.

The Algerian Sun: Setting as a Philosophical Character

Often overlooked in philosophical discussions is the visceral, physical reality of Camus's prose. The Stranger is drenched in the sensory overload of colonial Algiers. The blinding sun on the beach is not mere atmosphere; it is the agent of the murder. The heat, the glare, the physical discomfort—these are the absurd forces that trigger the fatal shot. Camus roots his abstract philosophy in the tangible world.

This emphasis on the physical underscores the absurdist belief that meaning is not found in transcendent ideals but in the immediate experience of the world, however senseless it may seem. The body's reactions—to heat, to desire, to fatigue—are as truthful, if not more so, than the mind's abstract rationalizations. This connection to the physical earth is a hallmark of Camus's work, distinguishing his absurdist fiction from the more cerebral traditions of other philosophers.

From Post-War to Post-Truth: The Stranger's Enduring Relevance

Why does a novel from 1942 still command such attention? Its themes have migrated from the post-war existential crisis to the core of contemporary digital life. In an age of curated social media personas and performative outrage, Meursault's refusal to perform feels radically relevant. We live in a world that constantly demands the correct emotional display, the proper alignment with trending sentiments.

The Stranger asks us: What is authentic feeling in a scripted world? It challenges the modern tendency to judge intent based on outward signifiers rather than actions. Furthermore, in a fragmented political and media landscape often described as "absurd," Camus's work provides a framework. He does not offer the comfort of easy answers or divine purpose. Instead, he offers the stark, difficult freedom of creating one's own meaning in a universe that provides none—a message that resonates with anyone questioning the narratives they are told to believe.

Common Misreadings and Critical Pitfalls

Several misconceptions can hinder a fruitful engagement with The Stranger. First is reading Meursault as simply a sociopath. This reduces the novel's philosophical depth to a case study. Second is viewing the ending as purely nihilistic. Meursault's final outburst is one of passionate, almost joyful, rebellion against the illusion of meaning. He finds a form of happiness in his lucid acceptance.

Another pitfall is separating the novel from its sequel-in-idea, The Myth of Sisyphus. While The Stranger illustrates the feeling of the absurd, the essay explicitly defines it and argues for revolt—the conscious maintenance of the struggle itself as a form of victory. Reading them together enriches both. Finally, ignoring the colonial Algerian context can flatten the narrative. The specific social tensions of the setting inform the characters' relationships and the system that judges Meursault.

Engaging with the Classic: A Reader's Pathway

Approaching The Stranger can be daunting. Here is a suggested pathway: First, read it for the sheer experience. Let the prose and the unsettling mood wash over you. Don't rush to "solve" it. On a second read, focus on the sensory details—the sun, the heat, the physical descriptions. Ask yourself how they influence the action and Meursault's state of mind.

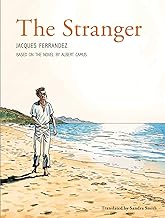

Then, explore the philosophical context. Camus's essay The Myth of Sisyphus is the perfect companion. For a deeper dive into this specific edition and its place within Camus's oeuvre, consider exploring The Stranger as a physical artifact, often containing insightful introductions and notes that contextualize the work. Finally, discuss it with others. The Stranger is a novel that thrives on debate. Does Meursault repel or attract you? Is he free or damned? There is no single answer, and the discussion is where the novel's true life resides.

Conclusion: The Liberating Challenge of Indifference

The Stranger by Albert Camus endures not because it provides comfort, but because it denies it. It is a classic literature precisely because it remains uncomfortable, a stone in the shoe of complacent belief. In Meursault, we see the terrifying freedom that comes from stripping away the stories we tell ourselves to make life coherent. The novel's final message is not one of despair, but of a hard-won, defiant lucidity.

In a world that often feels senseless, Camus does not invite us to find a pre-ordained meaning, but to have the courage, like Meursault in his prison cell, to open ourselves to the "benign indifference of the universe" and, in doing so, to become the sole authors of our own passion and our own revolt. This is the enduring power of this bestseller—it is a book that, once read, never fully leaves you, quietly challenging your assumptions long after the final page is turned.