Albert Camus's The Stranger stands as a towering pillar of 20th-century literature, a novel that distills complex philosophical ideas into a stark, compelling narrative. More than just a story, it is an experience—a confrontation with the absurdity of existence through the eyes of its unforgettable protagonist, Meursault. For readers encountering this modern classic for the first time, its apparent simplicity can be deceptive. This guide delves into the heart of Camus's masterpiece, exploring the character of Meursault, the core tenets of absurdist philosophy, and the novel's enduring legacy as a definitive work of existentialist fiction.

Who is Meursault? The Man Behind the Indifference

Meursault is not a hero in the traditional sense. He is an office clerk in Algiers, a man who begins the novel with the stark declaration, "Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can't be sure." This opening line immediately establishes his profound emotional detachment from societal norms. He attends his mother's funeral but feels no grief; he agrees to marry his girlfriend, Marie, but expresses no particular joy. His actions are driven by immediate physical sensations—the sun's heat, the taste of coffee, the allure of a swim—rather than by emotional or moral imperatives.

This detachment is often misinterpreted as simple apathy. However, a closer reading of The Stranger by Albert Camus reveals a man who is brutally honest, both with himself and the world. He refuses to lie, even when a lie would save him. He does not pretend to feel emotions he does not experience. In this sense, Meursault represents a radical form of authenticity, one that society finds deeply threatening. His trial for murder becomes less about the act itself and more about his failure to cry at his mother's funeral, highlighting how society judges conformity to emotional rituals more harshly than violence.

The Philosophy of the Absurd in The Stranger

The term "absurd," in Camus's philosophy, does not mean "ridiculous." It describes the fundamental conflict between the human desire for meaning, order, and purpose, and the silent, indifferent universe that offers none. The Stranger is the narrative embodiment of this conflict. The world of the novel is sensuous and vivid—full of sun, sea, and physical detail—yet it is devoid of inherent meaning. Events happen without reason: a friendship begins on a staircase, a murder occurs on a sun-drenched beach.

The pivotal moment of the novel, when Meursault kills the Arab on the beach, is famously attributed not to hatred or premeditation, but to the oppressive, disorienting glare of the sun. "The sun was the same as it had been the day I'd buried Maman," he reflects. This connection underscores the absurd: a life-altering act of violence is triggered by an indifferent natural force. The universe does not conspire; it simply is, and human actions within it are often irrational and disconnected from grand narratives of justice or fate. This exploration is central to understanding absurdist fiction as a genre.

The Trial: Society vs. the Authentic Individual

The second part of the novel shifts from Meursault's first-person narrative of events to his trial and imprisonment. Here, Camus masterfully critiques the machinery of society and justice. The prosecutor builds his case not on the facts of the murder, but on Meursault's character—his calm demeanor at the funeral, his quick romance with Marie, his friendship with the pimp Raymond. Society, represented by the court, cannot comprehend a man who lives outside its emotional and moral codes. They invent a narrative for him: a soulless monster who killed in cold blood.

Meursault's refusal to participate in this charade—to express remorse or seek salvation through God—seals his fate. His final outburst at the chaplain is a triumphant, albeit bleak, assertion of his truth: he has lived authentically according to the truths of the physical, absurd world. He finds a strange peace in the "benign indifference of the universe," embracing the certainty of his death as the only true freedom. This confrontation is a hallmark of philosophical fiction, where plot serves to investigate profound questions of existence.

Why The Stranger Remains a Modern Classic

First published in 1942, The Stranger's power has not diminished. Its concise, stripped-down prose style (influenced by American hard-boiled fiction) feels strikingly modern. Its central question—how to live an authentic life in a world without pre-ordained meaning—resonates deeply in an increasingly secular and complex age. Readers continue to see themselves in Meursault's alienation, his confrontation with bureaucratic absurdity, and his search for a personal truth.

The novel does not provide easy answers. Instead, it forces a confrontation. It asks us to examine the unspoken rules we follow and the emotions we perform. Is Meursault free, or is he a victim? Is his honesty noble, or is it a fatal flaw? Albert Camus presents the dilemma without moralizing, leaving the reader to grapple with the implications. This open-ended, challenging quality is what secures its place in the canon of classic literature.

Exploring Camus's Masterpiece Further

The Stranger is often read alongside Camus's philosophical essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, which formally outlines the concept of the absurd and proposes the ideal of the "absurd hero" who finds freedom and revolt in the relentless, meaningless task. Reading the novel through this lens enriches the experience, framing Meursault's journey as a tragic but coherent philosophical stance.

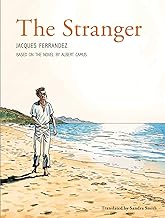

For those seeking to own a copy of this pivotal work, a well-crafted edition can enhance the reading experience. You can explore The Stranger to delve into the text that has challenged and inspired generations. Whether you are a student of philosophy, a lover of literary fiction, or simply a curious reader, Camus's novel offers a profound and unforgettable exploration of what it means to be human in an indifferent world. Its final pages, with Meursault's angry, joyous acceptance, remain one of the most powerful conclusions in all of literature, a raw shout of existence against the silence of the universe.